This weekend, and for the first time in their history, the Irish Prison Service will take part in a unique commemoration ceremony.

On Sunday 14th November, prison officers will commemorate the men who took part in one of the most significant events in the struggle for independence – the 1917 Mountjoy hunger strike. It was a hunger strike that won Irish republican prisoners political prisoner status for the first time; but also sadly resulted in the death of one of Ireland’s most distinguished revolutionaries – Tomás Ashe.

The commemoration will take place and the monument to the Claremen who took part in that hunger strike that was erected by the Mid Clare Brigade Commemoration Committee in 2017 at Monastery Park, Ennis.

The 1917 hunger strike formed part of a wider strategy that was developed by Patrick Brennan from Meelick, who was Brigadier of the Irish Volunteers in Clare. He wanted to reinvigorate the Volunteers after the 1916 Rising, as the movement had lost momentum. The strategy that he deployed was at first unique to Clare.

Parading and drilling had been made illegal after the Rising and therefore, where it did happen, it took place in secret. Brennan and other senior Volunteer officers agreed that parading and drilling would take place in public in Clare, with the certainty that the officers involved would be arrested. When they were arrested, they would not plead or recognise the jurisdiction of the court to try them, nor would they make and attempt to defend themselves. Once convicted and imprisoned, they would go on hunger strike for political prisoner status.

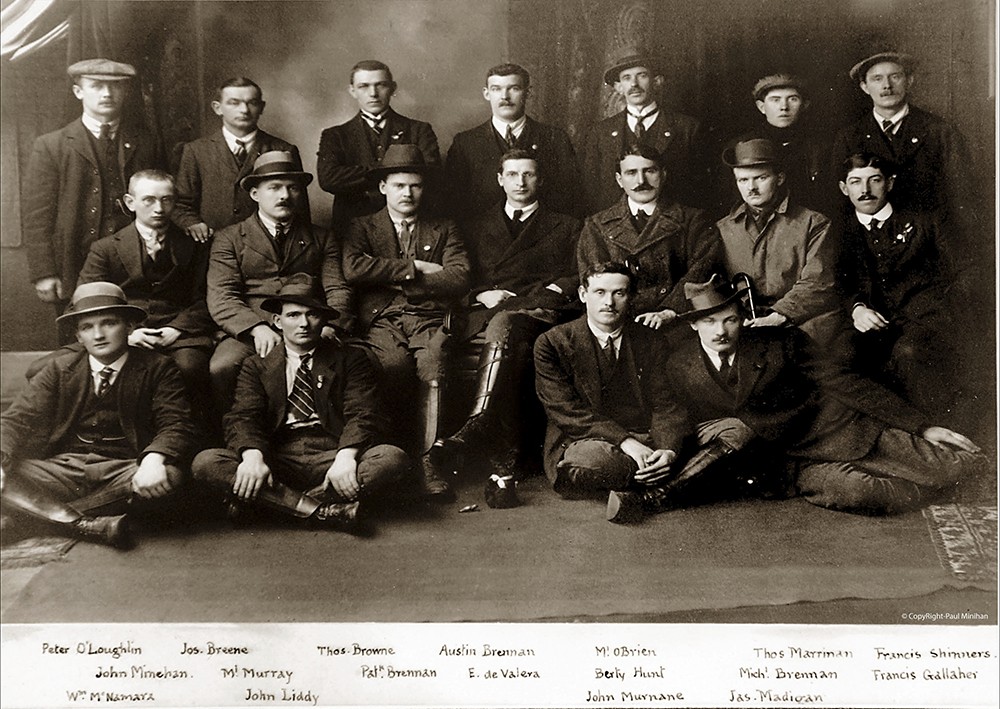

Drilling and parading commenced in July, and so did the arrests. The first to be arrested were Patrick Brennan and his two brothers, Michael and Austin, together with Peadar O’Loughlin of Liscannor. Other Volunteers were arrested throughout July, August and September. Patrick Brennan’s strategy was soon adopted by Volunteers nationwide, and other officers were also arrested in other counties.

Some of those officers were already under surveillance since the Rising, like John Minihan, Vice-Commandant, 5th Battalion, Clare Brigade, whose recently released British intelligence file contains detailed descriptions of his activities at Corofin, where he was observed drilling up to 115 men in addition to members of Cumann na mBan. He was arrested on 16th August.

Arrested officers were brought initially to Ennis Barracks and from there by train to Cork. Commandant Art O’Donnell, from Tullycrine, who was arrested on 14th August, tells us that large crowds had begun to attend at the railway stations to give the prisoners a send-off. They were all tried by courts martial at Victoria Barracks, Cork (now Collins Barracks).

Prison sentences ranged from six months to two years. Seven of the forty prisoners convicted received their sentences with hard labour, of which six were from Clare: John Liddy, Danganelly; William McNamara, 70 Cathedral Place, Ennis; John Minihan, Corofin; Sean Murnane, Newmarket-on-Fergus; Michael Murray, Newmarket-on-Fergus and Francis Shinners, Market Place, Ennis. The hard labour prisoners were held in C-wing and elected the seventh of their number, Tomás Ashe, President of the IRB Supreme Council, as their leader.

The thirty-three non-hard labour prisoners were held in D-wing and comprised ten from Clare: Patrick, Michael and Austin Brennan, Meelick; James Griffey, Cabey’s Lane, Ennis, Frank Gallagher, Knockalisheen; James Madigan, Jail Street, Ennis; H.J. Hunt, Corofin; Arthur O’Donnell, Tullycrine, Labasheeda; Michael O’Brien, Ruan; and Peter O’Loughlin, Glebe Lodge, Loughaloon, Liscannor. They choose as their leader, Austin Stack, County Kerry, who was also overall in charge of all the prisoners.

The prisoners made demands for political prisoner status, demanding not to be treated as criminals. On 17th September, the hard labour prisoners in C-wing commenced a campaign of disobedience in pursuit of their aims. They refused to do any work or comply with any prison rules and, as a consequence, they were placed in solitary confinement on bread and water. The following day, the non-hard labour prisoners commenced in a similar campaign.

The prison authorities responded by moving all of the prisoners to C-Wing. The prisoners continued to escalate their protests by ringing prison bells loudly and breaking windows, beds, stools, and fittings. The wardens responded by stripped the prisoners of their boots and removing all cell furniture, including beds and bed clothes, and leaving only the Bible, a prayer book and salt.

A hunger strike was commenced by thirty-eight of the prisoners, and this included all of the Claremen mentioned. The hunger strike began on 20th September, and on 22nd September the prison authorities started a regime of force feeding each prisoner twice per day. This involved dragging each prisoner from his cell, strapping him to a chair and forcing a tube down his throat through which liquidised food was pumped. The process was grotesque and painful. It was also dangerous. On 25th September, Tomás Ashe died a painful death while being force fed – where-by the liquid entered his lungs instead of his stomach.

The reaction to Ashe’s death was immediate and overwhelming, both nationally and internationally. It was extremely embarrassing to the British authorities while greatly bolstering support for Sinn Féin. Even the official report of the formal enquire into the death of Ashe and the treatment of the prisoners, was scathing of the authorities. In advance of Ashe’s funeral, the authorities sought to restrict rail access to the capital, but it proved a futile effort and Ashe’s funeral was the largest that was seen in Dublin since that of Charles Stewart Parnell.

Force feeding ended on the 29th September, and when the authorities granted the prisoners political prisoner status, the hunger strike ended on 30th September. This was a major milestone in the struggle for independence and was a historic victory for the Volunteers and Sinn Féin.

On the 13th November, the prisoners were transferred to Dundalk Prison. A second hunger strike commences immediately when it became clear that the authorities were reneging on some of the concessions that had been granted at Mountjoy. The sixteen original Claremen were joined in their hunger strike at Dundalk by Joseph Breen, Tiernaglehane; Thomas Browne, Bank Place, Ennis and Thomas Marrinan, Ballyduffbeg, Inagh.

Between the 15th and 17th November, the authorities released the prisoners under the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act, 1913 – more commonly known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, because this legislation allowed the authorities to re-arrest the prisoners once they had regained their health. Upon their release, the prisoners attended a number of formal receptions in their honour in Dublin before returning to Clare to a heroes’ welcome, where-by thousands turned out to greet them.

Though largely overlooked in recent decades, the 1917 Mountjoy hunger strike and tragic death of Tomás Ashe was hugely significant in Irish history. It was one of the most pivotal events of the period between the 1916 Rising and the ambush at Soloheadbeg, that marked the beginning of the War of Independence in 1919. It reinvigorated the Irish Volunteer movement and was hugely instrumental in securing support for Sinn Féin in the lead-up to the 1918 general election; an election that transformed the Irish political landscape.

Sunday’s ceremony will commence at 12 noon at the monument to the Clare Mountjoy Hunger Strikers at the Monastery Park, Ennis (near Glór).

It will also be attended by representatives of the 22nd Infantry Battalion and the Mid-Clare Brigade Commemoration Committee. All are welcome.